My fascination with climbing began with tiny me clambering up massive piles of dirt in our burgeoning subdivision. Muddy mountains towering over the backyard, pleading to be conquered. That love of climbing followed me into the trees. Up concrete bricks stacked high behind my grandmother’s sewing shop. Above the playground on a pyramid of elastic ropes. Sure, there was a brief decades-long detour into a crippling fear of heights that left me feeling anxious at the sight of a roller coaster. Where flying in a plane became an exercise in managing manic mayhem that scrambled my brain and left me teetering on the edge of insanity. I maintain to this day that that fear is semi-rational, for I am not a bird. I do not belong in the sky.

But the allure of the climb persisted. And while my anxiety kept me firmly rooted to the ground, my love of video games enabled me to live vicariously through avatars. Obviously, like, yeah, playing a game is not the same thing as, you know, doing the thing, but there’s still a satisfaction in steering a character via controller, watching them flip and fly and sail through the air, scale impossible structures, or swing between skyscrapers. Performing feats that most people can only dream of. The fantasy is, in many ways, meaningful. Not a replacement for the act, but a new perspective on it. And gaming gave me a plethora of perspectives. I remember the thrill of Spider-Man 2 on the Xbox, zipping through the New York skyline. I remember the promise of Assassin’s Creed, grinning as I guided Altaïr up the ornate stone façade of a cathedral. I remember the parkour of Mirror’s Edge or Dying Light. That visceral feeling of just barely making a jump or narrowly escaping the clutches of a zombie by skittering across the rooftops. And while I loved these experiences for myriad reasons, I did always feel myself wanting something… more. Maybe the limitations of the games were too stark at times, like when you were climbing a mountain and each hold was marked by some yellow paint or weird symbol, where “climbing” was just something your character did while you tilted the thumbstick in a certain direction, maybe pressing the A button once in awhile. There was no technique. No skill. No tension. And it was that lack of tension that made it feel more akin to a chore. There’s very little that’s immersive (or fun) about holding a thumbstick forward and watching the illustrious hero huff and puff up a cliffside.

And so at a certain point, I began to wonder if video games could even accurately capture the thrill I experienced as a child, where just dangling from a branch of a tree could be exhilarating. I continued to play games that pushed the boundaries of what was possible, even hoping that someone would finally crack the experience in VR. But, sadly, these experiences largely left me feeling empty. I’d have to look elsewhere.

That search led me to discovering a love of Bouldering in my mid-30s. It was the first and only time in my entire fucking life when exercise felt fun. Bouldering presented an opportunity to strengthen me not only physically, but mentally. I quickly learned just how important technique was. For as much raw strength one may possess, if you don’t learn how to leverage your limbs to their fullest potential, you’ll be left muscling your way up, straining through gritted teeth, hoping you possess the stamina to send it. There’s a reason Bouldering routes are called “problems.” You are meant to solve them. More often than not, relying solely on brute force won’t get you very far. It was that element that made climbing in a gym instantly click with me. The more I thought through a problem, the more likely I was to solve it. That lack of thoughtfulness was exactly what made climbing in video games feel so dull.

Cairn is the first video game I have ever played that has managed to crack the tension and technique of climbing.

“Hey, Keenan,” you say. “I clicked on a link that said it was a review for Cairn, but you haven’t even brought Cairn up and you’re nearly 700 words into this thing. What the hell—”

Cairn is the latest from French development studio, The Game Bakers. It is a game about Aava (like “guava”), a famous climber embarking on a journey up Mount Kami, a climb defined by its danger, as is evident by the sheer number of people who have died attempting the ascent. Together with her trusty robot companion, she’ll overcome tough challenges and, in the process, learn what’s truly important. Okay, pretty straightforward video game stuff. Time to get to the top of the mountain!

The most notable thing about Cairn is how it simulates climbing in a way that I would describe as about as close to the real thing as you can get. Controlling Aava isn’t about pressing the thumbstick in a certain direction and watching fancy dynamic animations automatically propel her up a crag. Instead, you control her using a simple scheme of moving an individual limb with the thumbstick and pressing X or Square to place it, then switching to the next one (the game does a fine job of managing this automatically, though you can enable manual limb selection for those moments where you need more in-depth control), manipulating her hands and feet one at a time to methodically scale cliffs. It’s a pretty remarkable mechanic, even when the video game of it all makes itself apparent. Limbs sometimes twist themselves unnaturally as she searches for a foothold, or clip through each other (or rock faces), resulting in some truly bizarre contortions. It’s in these moments where it feels like the entire system is on the verge of crumbling under its own ambition. But, for me, it’s hard to get too hung up on the quirks when the game otherwise feels so good to play. I appreciate that the team took a big swing and aimed for authenticity, even if the seams show a bit. The way Aava adjusts, how she pushes and pulls, the way she dynamically changes her positioning. It’s obvious that the devs took great care in studying how climbers actually climb. The result is a simulation that looks and feels uniquely accurate.

As a result, Cairn is the first video game I have ever played that has managed to crack the tension and technique of climbing. It is not a game about leveling up or allocating skill points or increasing your strength number so you can climb harder routes. It is about using your brain to puzzle out the best way to control Aava and get her to the top. You place a foot in a crack, another on a slope, reach a hand up to a pinch, and the other to a jug. You then move the first foot to match it with the other, switching out to flag, while you reach up to a ledge with a hand to steady her. Then you hook her heel onto a different ledge, and finally leverage the strength and sturdiness of her thighs to propel her upward and reach for the next set of holds. All the while, you’re reading her body language, listening to her breaths, watching as her limbs twitch and spasm if she’s not well-positioned. You see her struggle as her arms get pumped. You hear her cry out as she exerts all of her effort to reach out and grasp the ledge before pulling herself up onto some solid ground to take a well-earned breather. There are no status bars. There is no (default) way to determine what holds are stable. You learn by observing, and the more effectively you position Aava on her climbs, the less effort those climbs will take for both of you. There’s nothing quite like reaching the top of a route and feeling your entire body unclench as you let out a long sigh, a sensation I typically associate with the most challenging of fights in something like Sekiro.

One thing I was continually in awe of is just how many different routes are available to facilitate her ascent, ensuring that no two climbs will ever be the same. There are smooth, sparse faces with very few obvious holds. There are cracks that web their way up the mountain, providing almost a natural ladder that are much easier to send, and there are sprawling, jutting crags that meander horizontally as much as vertically. The design of the mountain feels organic in a way that few games attempt to simulate. It’s even possible to chimney climb, where you make your way upward by pressing your hands and feet against parallel walls, the only thing keeping you from plummeting is the friction generated by your stiff limbs. When I say this is exhilarating, I could not be more serious. The fact that this is even possible is wild.

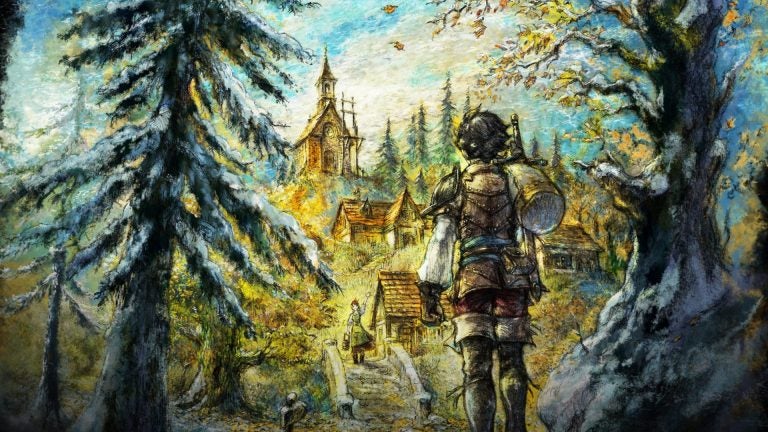

What helps all of this is how the game presents itself visually. The art style is painterly, akin to a comic book, with pronounced cel-shaded outlines adorning characters and rock features. It’s not only stunning to look at, but also serves a functional purpose in naturally highlighting otherwise invisible holds. In climbing, being able to hook a finger or two into a pocket, or your toes onto a crimp, is often the difference between success and failure. The fact that you can plan your route and see these almost imperceptible holds perfectly encapsulates how art direction can amplify gameplay in a meaningful way. Where most games might have you click a button to highlight the holds in your route through some sort of ClimberVision™ contrivance, Cairn opts for the minimalist approach, trusting in its visuals to help the player make the best decisions. And you’ll want to consider all of these little details as you climb to make your life easier. Not easy, but easier.

The Game Bakers specifically say that they intend for Cairn to be a challenging experience, testing player’s wits and skill as they scale Kami. As if the core climbing experience wasn’t enough, there are survival mechanics thrown in, with hunger, thirst, temperature, and health bars to consider in between rests at your trusty bivouac (which also serves as a save point). Neglecting any of these can cause Aava’s performance to falter, making climbs even more difficult.

Consumables often serve a secondary purpose as well, temporarily boosting stats like Focus or Grit to help you overcome your next climb. Munching on a granola bar or, I dunno, a dandelion could provide just enough extra Focus to get you through a tough route. Personally, I found the balance to be such that I never felt like I was left scrambling to find food, but there were a couple moments where I was rummaging through my rucksack (which is a novel little physics-based minigame in and of itself), trying to determine what to get rid of to make space for other items I might need later. Should I eat these mashed potatoes now to make room for more painkillers? Should I stow yet another package of chalk? The question of what and how much to horde definitely came up more than once, and looking back, I think maybe I worried about it more than I needed to. There’s usually enough stuff to keep you topped off, especially if you spend a little time in between your climbs exploring your surroundings. You might find some dead climber’s abandoned backpack, or some dead climber’s abandoned tent, or some dead climber’s abandoned body, which you can then scavenge for whatever goodies they’ll no longer need.

Thinking about my experience playing through the game (it took me just under 10 and a half hours to reach the credits, though the devs anticipate completionists could take around 30 as you uncover all of the little secrets hiding in nooks and crannies and caves), I do wonder how much of these survival mechanics were absolutely necessary to include. I haven’t even mentioned the fact that you have to keep an eye on the status of Aava’s individual fingers. No, I’m not joking. They get torn up over time as she climbs and need to be taped up (another item to keep in the bag) with a pretty annoying bit of joystick twirling. There’s also a whole cooking mechanic where you combine a liquid with a not liquid to create meals with bigger boosts. There’s also a way to compost the garbage you create (or find littered about the mountain) and turn it into more chalk (the one consumable I did find truly useful). There are pitons to drill into the rock. There are weather conditions to be mindful of. There’s a whole day/night cycle. It all feels a bit overstuffed perhaps. I wouldn’t say it ever devolves into tedium, but I’m not entirely sure if it is successful in adding to the enjoyment of the simulation. The stress and tension typically present themselves in how you approach each climb, not whether you’ve crafted the optimal meal.

In fact, once I finished the game, I immediately started up a new save and turned the survival stuff off in the accessibility menu and realized I had just as much fun focusing on experimenting with new ways to approach my climbs. Yeah, sure, it’s maybe not as “realistic” or “immersive” to go days without eating, but it’s also a video game that has something so special and interesting in its core mechanic that maybe all the little extra fluff wasn’t needed.

But I do have to laud the fact that Cairn provides plenty of opportunity for the player to craft the experience they want to have. When starting a new game, there are three difficulty options to choose from: Explorer, Alpinist, and Free Solo. Explorer makes the survival stuff less demanding and turns on some assists by default, including the ability to rewind time in the event you fall. Alpinist is the “intended” experience, and Free Solo is the option I’m sure will make for some truly entertaining YouTube videos, because it disables the use of pitons as well as the ability to save. When you inevitably fall and break your neck, that’s it. Time to start over. Just like real life!

Truthfully, I wish there had been a difficulty level between Alpinist and Free Solo for my first run. I didn’t want to risk dying and having to restart all the way at the beginning, but I also didn’t want to be tempted to rely on belaying, hoping for a more “pure” climbing experience—whatever the fuck that means. So I set off with a personal challenge to myself to free solo this thing, which was, UM, A LITTLE FRUSTRATING AT TIMES. Especially in the moments where I could swear that Aava was standing steadily on some substantial holds, only to slip and fall to her death.

Moments like that were admittedly rare, though I did realize at a certain point that my personal challenge was getting in the way of having fun. I found myself questioning what the purpose of it was. Why had I set up such strict demands? Who was I trying to impress? What was I ultimately going to get out of failing over and over and over? Don’t get me wrong, I love a challenging game, but there was a moment playing this where I realized that I wasn’t here to beat my head against a wall. I wanted to enjoy the climb. And when I realized that I was, in fact, the problem, I got out of my own way and the pure joy of the game became easier to grasp.

Which I think more or less mirrors Aava’s journey. She starts off as someone who is pretty unpleasant, her own ambition driving her to eschew her responsibilities, ignore the people who care about her, and miss out on important moments in her life. Her hardheadedness, her stubbornness, her inability to see beyond her obsession. It’s all so very fucking relatable in a way that feels like a personal attack, The Game Bakers, and I do not appreciate it!

But I, at least, possess enough self-awareness to recognize when I’m just being a stubborn asshole, and that’s when I can check in and say, “Alright. I’m just here for the fun.” It’s that mindset shift that got me through, when the game truly began to feel meditative and satisfying. Where things started to click. It made me a better climber, and helped me persevere.

It’s also what caused me to ultimately butt heads with Aava in her journey. At a certain point, everything the game was telling me made me think I ought to stop, but my own desire to keep playing drove me forward. A contradiction that I still feel as I think about it now. How much do we let our expectations and desires drive us, even if we know it’s not the “right” thing to do? At what point do we allow ourselves some reprieve, even if it means giving up before seeing the end? What does it mean to have enough? What are we willing to sacrifice to attain our goals? The story of the game left me with many more questions for myself than when I initially started. Depending on how much introspection you do or do not want to engage in, this might piss you off! I dunno! I’m not your therapist!

Oh, also (and I am legally obligated to write this, lest I be drawn and quartered for—gasp—omitting performance stuff from a video game review), the game runs well! I played most of it on my main rig, where it typically ran well over 60 FPS at the highest settings, with only the occasional hang or stutter. There were two or three notable moments where the framerate struggled for a bit, usually when bombarded by heavy particle effects (or when looking at that one particular rock face—you know who you are and what you did), but this was rare and nothing that seemed to affect the actual gameplay. It is, overall, a highly polished experience. I played with both an Xbox Series controller and a PS5 DualSense. Both work well. I was not brave enough to try mouse and keyboard, and the “Controller recommended” splash screen as you boot the game leads me to believe I made the right choice. I also played a couple hours on Steam Deck OLED with the TDP Limit set to 10W, which gave me a nice balance between performance and battery life. I imagine I’ll keep it installed on there for awhile. It’s a great Steam Deck game.

Keenan's PC Specs:

Cairn is so fascinating to me. It’s a stunningly beautiful simulation that captures the magic of climbing in a way no other game ever has. It’s also something that feels like maybe it’s trying to be more than it needs to. Its ambition is readily apparent in all of its systems and secrets and details. Hell, it features a lovely soundtrack that is used so sparingly, I often forgot it was there, and I don’t know exactly how I feel about that choice. Would it have been better to have a cinematic score sweeping me along as I scaled the mountain? Or was it more impactful because it showed up solely to punctuate the milestones in my journey? Would the ending still have moved me to tears had I been inundated by a melodic soundscape the entire way? I don’t really have a good answer for any of that, but I know that I’ll be thinking about this experience for quite some time.

Early last year, I started experiencing increasing pain in my hands after I climbed at the gym, and I decided to take a break and recuperate. When the physical pain eventually subsided, I felt the all-too-familiar emotional weight in its place. The anxiety. The worrying: “Can I do this? What if I get hurt again? Is it worth the risk?” I haven’t climbed since. The fear won.

When the demo for Cairn was released, I lost hours to the little taste it presented. And playing the game in its entirety over the course of the last week, I came to realize that the reason I loved it so much was because it connected with that part of me that longs to be on the wall, solving problems. The thing I’ve looked for in countless games over the course of decades. A reunion with the kid who stood on top of that dirt mound, alone and satisfied. No, playing a game will never be the same as doing the thing, but Cairn helped me stay in touch with something I thought had been lost. It’s hard to imagine what more I could possibly need. I feel complete.