Longtime followers of Hideo Kojima’s work know that his games have a reputation for being multifaceted journeys that are as frequently confounding as they are astounding. We go along for each new ride fully aware that we are setting ourselves up for amazement and moments of frustration, and that the experience is often about accepting and even inviting both extreme ends of this spectrum, and everything in between.

Death Stranding is Kojima’s first foray into something truly new in well over a decade (not counting the ill-fated but well-loved P.T.), and the question that has largely been hanging over the release of this game is “Can it stand apart from Kojima’s legacy?” Or, more pointedly, “Can Death Stranding escape the shadow of Metal Gear?” Given that Death Stranding originally released on consoles in 2019 and there has been plenty of time for players to evaluate these questions and come to their own conclusions, I won’t spend overly much time on this particular point, except to say this: Death Stranding‘s parallels to and influences from the Metal Gear series are inevitable.

Every aspect of Death Stranding is informed by Kojima’s prior works, for better or worse, both in the ways that it borrows from Metal Gear‘s box of tricks and the ways in which it deviates. Kojima has been given a level of freedom to explore that he’s not had in ages, and the choices he makes about what elements of his style persist in his works and which are specific to individual creations will ultimately define whether all of his games are derivative of Metal Gear, or if Metal Gear and Death Stranding are iconic pillars of Kojima’s particular brand. Only time and Kojima’s subsequent works will truly be able to shed light on this. For now though, Death Stranding predictably feels very familiar and also very alien.

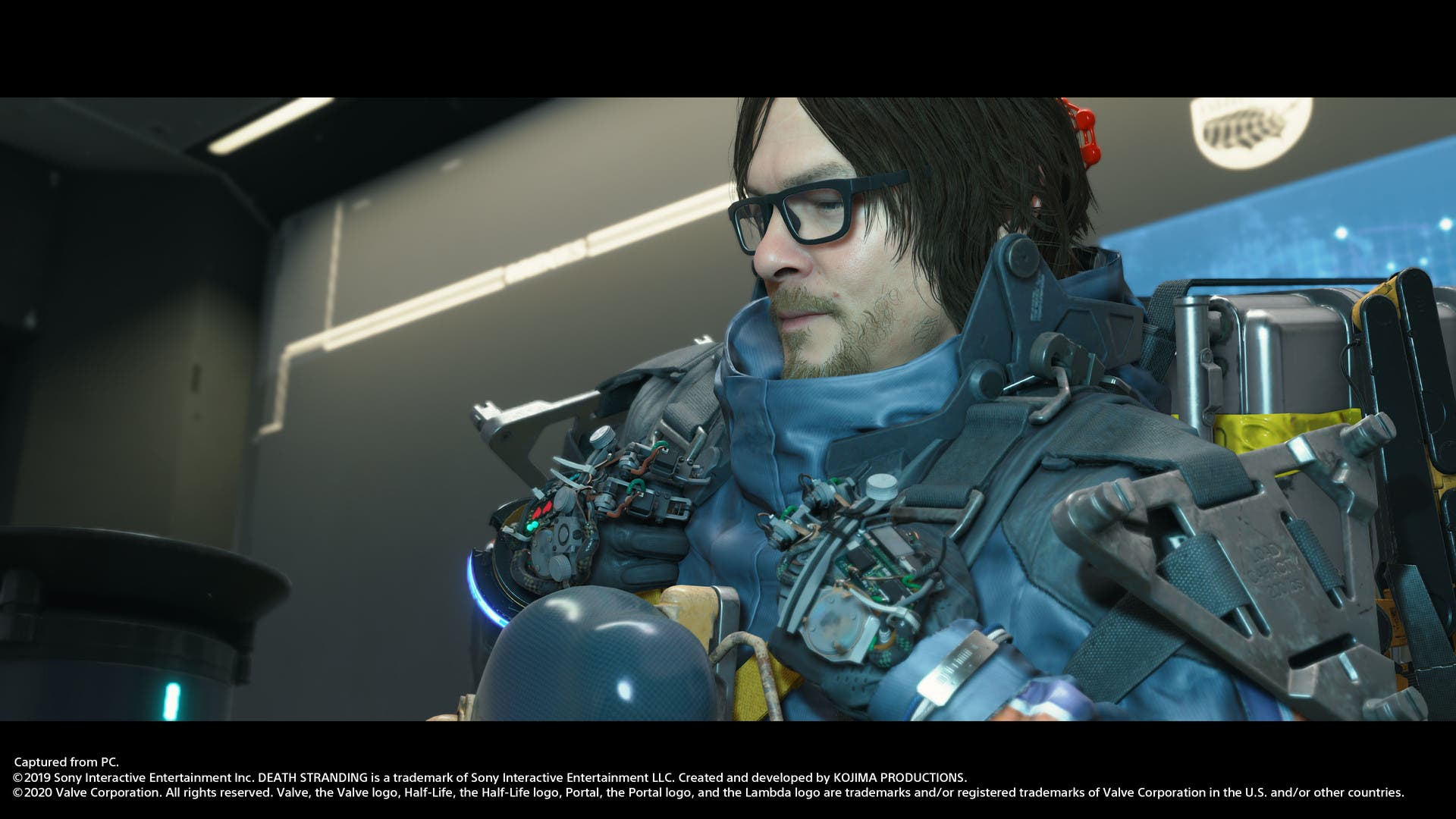

But what is Death Stranding, anyhow? You’ve no doubt seen the massive reviews from its initial release, some of which take a literal hour to read, which explore all of the things the game is and is not. Even if you haven’t, word of mouth has no doubt painted some sort of indecipherable tapestry that you hang in your mind, taking sidelong glances at and eyeing warily as you mull over whether or not to engage with its mystery. Let’s strip it down to the superficial analysis, at least, for the sake of consumption. Death Stranding is an action game with a heavy emphasis on story and cinematics, and game play which centers chiefly around stacking way too much stuff on yourself so you can carry it across a bizarre alternate version of the United States making deliveries and reconnecting the future super internet, which by the way may have some unsettling connections to the world of the dead. You walk around a whole lot, you gaze at gorgeous landscapes, you get into extremely tense stealth sequences involving invisible specters of the dead, and you spend an inordinate amount of time having nonsensical jargon thrown at you which the game may or may not ever actually explain to you so much as expect you to figure out on your own from context.

If this sounds mildly hostile to the player, it only barely is. For as seemingly disorienting as all of this may sound, Death Stranding does an excellent job of slowly introducing and adding systems, giving you time to get comfortable with each game play element before adding another layer on top, and allowing you to learn how each of those systems interoperates. It’s not quite like a traditional “tutorial,” so much as slowly adding complexity in a way that feels more natural and gives you time to explore with remarkably low pressure (in most cases). If anything, the systems and the ways in which you interact with Death Stranding are incredibly well defined and instructed, and most or all of the games obtuse nature comes from its story, which is bizarre and also strangely gripping.

The more time I have spent with Death Stranding, the more I have come to realize that for as much control as Kojima and Kojima Productions like to have over your game play experience, to some extent you can define exactly what this game is to you. You can choose to treat it as primarily a narrative experience punctuated by gameplay that exists to move things forward. You can choose to put the story on hold as often as you like and focus on playing it as a walking and/or delivery simulator. You can slow down and engage in meditative moments as you trudge up a rocky scramble and pause to take in a stunning new vista. You can focus entirely on building out infrastructure. You can do all of these things interchangeably and alter the pace of the game to suit your mood as you go, which in some ways is reminiscent of Metal Gear Solid V‘s experience (up until the latter half when the story became somewhat anemic). Somehow, it all actually works, in ways I don’t fully understand, but that I appreciate nonetheless.

Worth noting is that the game leans heavily on the concept of “likes” for interacting with the world, both in those you receive for performing actions and placing assistive structures, and those you give to other players in the asnychronous, collaborative world exploration effort built into the game. The way that online play and interactions with other players works in this game is exceedingly clever, giving you a feeling of being in a world full of other explorers even though you will never actually see one another. There are artifacts of other players’ journeys everywhere, and the impact of making you feel significantly much less alone in what is an otherwise very solitary journey cannot be understated. Of course, the other side of this coin is that it can be easy to slip into a pursuit of “likes” for your efforts, as they have indirect effects on your experience, and “likes” in Death Stranding are both a fun, harmless system to engage in and a not-so-subtle commentary on social media culture that rings with eerie truth even more in 2020 than it did eight months ago when the game first released.

I would be remiss if I didn’t take a moment to talk about the BB (Bridge Baby), and your relationship to it as both Sam and as yourself, the player. Make no mistake, Death Stranding deals in some extremely uncomfortable themes and concepts, and the notion of keeping infants prisoners in fancy carrying cases purely for their ability to help “normal” humans detect the presence of BTs (the aforementioned spooky ghosts) is beyond unsettling. As you learn more about how BBs work, and the way they are treated as utilities rather than people, all while you continue to form a bond with yours, the worse that sinking feeling in your stomach gets. I found myself feeling very protective of BB early on, and highly responsible for keeping it “in service,” despite (or perhaps because of) the stress inflicted on it by its role in keeping us both alive. This is of course entirely by design, but as a parent these notes struck me with particular intensity.

Of course, the thing that we’re really here to discuss is not a retread of all of the other takes on Death Stranding that have been lurking on the internet for ages. What we need to dig into is the game’s PC performance.

Death Stranding was a highly ambitious game technically on the PlayStation 4, and given how impressive its quality was on that hardware, and knowing what compromises had to be made along the way to achieve that on Sony’s console, there was a lingering question of what the experience would be on PC hardware, and how much more taxing (or more capable) the game would be in a different ecosystem. It shouldn’t really be surprising, but the fact is that Death Stranding runs remarkably well on PC, and even with four year old hardware, the game outperforms its console counterpart to an impressive extent.

Tested on my system with an NVIDIA GTX 1080, an Intel i7 6700K, and 32GB of RAM, Death Stranding easily maintains 60 frames per second or more at 1440p, at a level of visual quality that frankly outstrips what the PS4 is capable of. Gone is the checkerboard rendering from the console version, and instead there is a crystal clear picture rendered in stunning detail with impressive effects and remarkable performance. In my time with it, the game has not faltered in the large open world or in city environments; it feels like an incredibly well optimized package, with a great deal of time and care invested into ensuring a smooth experience for the player. Prior to installing Nvidia’s Game Ready drivers for Death Stranding, and prior to the initial patch, there was a small amount of odd stuttering in certain scenes, but performance smoothed out completely with both of those elements in place. I am incredibly impressed with the PC release of Death Stranding from a technical perspective, and this is a very strong indicator of what the Decima engine will be capable of when future games utilizing that tech come to the PC.

I’ve said a whole lot about Death Stranding, but I don’t know how much clarity any of it actually provides. That’s sort of the nature of Death Stranding itself, and it is difficult to define or pin down into anything that is easy to communicate about succinctly. It is significantly more than the sum of its parts, but talking about what that holistic experience in a coherent way is incredibly difficult, which in turn makes talking about the overall quality of the thing also difficult.

When talking about the question of “Is Death Stranding worth my time and money,” it’s best to reframe that in the context of where the game’s value opportunities are, and determining if those elements are important to you personally. To that end, what I can say from my experience is that Death Stranding is a game with extremely high production values that tells a story on a grand scale with incredibly high stakes. The story itself is well written and fun to follow, even if it is difficult to get your head around at times (which is to be expected from Kojima). The game’s cast is strong, and the performance capture is extremely well done, so that it really does feel in most cases as though you’re engaging with a big budget sci-fi film. The gameplay mechanics are largely well designed, even if there are a lot of concepts to wrestle with, and the parts of the game where you’re actually playing feel weighty and rooted in something real and wondrous, despite the fantastical nature of the game’s backdrop. This is a well-polished experience sporting some truly excellent interface and world design, and the way the storytelling is integrated with (and also separated from) the act of playing the game feels surprisingly good. This is a game about world building, both literally and figuratively, and somehow, for me, all of it works fairly well.

As I’ve played through, I’ve asked myself on multiple occasions, “do I like this game?” and every time the answer I gave myself was “I think so?” Still, even in the early stages of playing when I felt most confused, I found a lot of reasons to be excited and interested. Only after multiple sessions with the game time away to think on those sessions have I been able to coalesce my thoughts about it and find ways to try and define my experiences with it. I think that qualitatively speaking, there are many ways in which Death Stranding is objectively good. I think there are also ways in which Death Stranding is subjectively either very good or very uninteresting, but never is it “not good.” I do think that even if it doesn’t seem like “fun” in the traditional sense (and to be clear, there is no shortage of Kojima’s signature quirk within), it is a fascinating experiment that has to be experienced first hand to be understood.

A Steam code for the game was provided by the publisher for review purposes